First it was the dotcom bubble. Then the Wall Street and housing bubbles. Is the education bubble next?

To be honest, I hadn’t realized there was such a thing as an “education bubble”. As the parent of three young adults, I can personally attest to experiencing the inflationary trend in higher education. Heck, we’re still helping our youngest pay back her student loans. But something I read last week got me thinking about it, and then I did a little more research. Just Google it yourself – over 57 million hits. Obviously there’s something out there, even if it’s still flying mostly under the radar.

Okay – so exactly just what is this “Education Bubble”? Basically, it refers to the concept of the increasing cost of higher education that has been nurtured by a societal belief in the unarguable value of a college degree at any cost compounded by the availability of easy credit. If you’ve spent any time surfing the net, you’ve seen the ads offering thousands of dollars in student loans to low-income adults and even homeless people. Like that’s a real smart risk on its face.

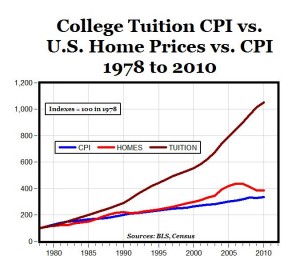

The chart above certainly illustrates the cost component of the equation. “How high can it go?”, you may be thinking? Who knows – but that’s not the part that should concern you most. Oh, no – it’s the Department of Labor’s one sentence prediction that should raise the red flags about the coming collapse – “Over the next decade, there will be fewer new jobs requiring college degrees than there will be new college graduates.” Dang. That old supply/demand thing rears its ugly head.

From Glenn Reynolds at Instapundit:

The money and time you spend on college matters. College education is so universally viewed as such a great investment that the cost and its return on investment get too little scrutiny. The statistics that trumpet the value of college are generalized in ways that tend to obscure the reality. A typical statistic cited is “the expected life time earnings of a bachelor’s college graduate are $2.1 million and the expected lifetime earnings of a high-school (only) graduate are $1.2 million (Day and Newburger, 2002)â€. This statistic, while impressive, ignores many other factors. When a student borrows large amounts of money to finance a poorly planned education, he or she can be put at a big disadvantage for many years to come. The availability of student loans, grants, and other financial aid has made college education possible for many more people than ever before. However, the availability of this money has created a large group of people who borrow carelessly with little or no planning, and without setting realistic goals or objectives.

It’s not unusual to hear of recent college graduates with $100,000 and more in student loans unable to find a job that pays more than $10-15/hr., with little prospect for advancement anytime soon. The average cost of a degree from U of M, MSU, or MSU-B in 2009 was over $75,000. And there aren’t a whole bunch of high-paying entry level jobs just waiting around for a new grad to step into. It’s tough to live on even $30 grand a year when the student loan payment is over $500 per month.

So why has the cost of a college education gotten more expensive?

A recent Money magazine report notes: “After adjusting for financial aid, the amount families pay for college has skyrocketed 439 percent since 1982. … Normal supply and demand can’t begin to explain cost increases of this magnitude.” Consumers would balk, except for two things. First — as with the housing bubble — cheap and readily available credit has let people borrow to finance education. They’re willing to do so because of (1) consumer ignorance, as students (and, often, their parents) don’t fully grasp just how harsh the impact of student loan payments will be after graduation; and (2) a belief that, whatever the cost, a college education is a necessary ticket to future prosperity.

Bubbles burst when there are no longer enough excessively optimistic and ignorant folks to fuel them. And there are signs that this is beginning to happen already.

Here’s the real question for us – what does this mean for Montana’s university system and for our current crop of high school students? Should the Board of Regents start trimming back some of the “Do you want fries with that?” college courses and focus on the degree programs that offer a reasonable return on investment for the cost of the education? Should we, as taxpayers, start getting serious about demanding our K-12 schools actually teach students the basics so that colleges aren’t forced to include remedial classes as a standard part of the freshman curriculum? Should we, as a society, begin to admit that not every kid has the aptitude or mental ability for college? Should we, as adults, finally admit the the purpose of a basic education is to provide students with the skills necessary to earn a living and provide for themselves and their families – and maybe start evaluating our investment in public education not in terms of cost, but rather in terms of value – to the student and to society?

Should we, as Montanans, maybe do something proactive to prevent the bubble from bursting and ruining the future for a generation of our kids?